A brief introduction to leather

I recently took part in a course through the Canadian Bookbinding and Book Arts Guild (CBBAG). This course is one of the many they offer, and is a prelude to their level three bookbinding course, in which students learn to bind in leather. Our instructor was Dan Mezza, a well known and highly sought-after bookbinder in the London, Ontario area. Taking lessons with Dan is always a pleasure as he truly knows the topic! Dan was a paper maker before he became a bookbinder.

Our introduction to leather was a three-day long course spanning a weekend. In this course we learned a bit about the history of leather, the types of leather used in bookbinding and how to properly pare leather and apply it to the board. We made a plaquette in the end for demonstration purposes.

Before we got started, we discussed what leather was, and the process used to make the leather we use for binding books. I’ll share a little of that here.

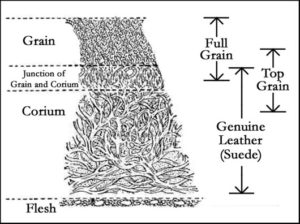

Leather is skin, common to all animals. Dan even showed us a book from fish skin and kangaroo skin. Leather is created by removing the hair, hair root and epidermis (surface layer of hard dead cells). These three layers are removed in tanning and the following are kept for leather: grain (outer layer from surface to hair root), corium (large fibre bundles interwoven at a higher angle towards the surface), and the junction of the grain and corium (this is different for each animal and the size of hair in an animal determines the strength of the leather).

A cross section of cowhide to give you a better idea of the layers (Image credits: vanderburghhumidors.com)

A cross section of cowhide to give you a better idea of the layers (Image credits: vanderburghhumidors.com)

There are two different processes we discussed for how leather is treated: tanning and tawing. There is also the process of turning skin into vellum/parchment.

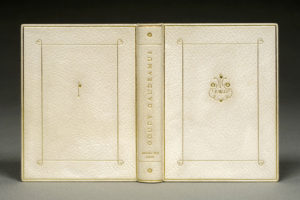

It is important to note that tawing is not tanning and the hides are treated differently. For tawing, the hides are treated with aluminum salts plus egg yolk, flour, and other ingredients. This technique was used in Egypt before it became widespread in Northern Europe in the Middle Ages. It has good handling properties, and is generally left white. This is where the term “White Library” is from, as before the 1500s everything was bound in tawed leather. “Brown Library” came after when tanned leather began to replace tawed. If the tawed leather gets wet it turns into rawhide, so as long as they don’t get wet, the bindings in tawed leather can last hundreds of years.

Example of alum tawed (image credit: https://guildofbookworkers.org)

The tanning process is rather different; Dan argues that the best leathers are from the early 1800s, as anything after the Industrial Revolution begins to face deteriorating problems. Before the 19th century most leather was tanned with oak or other vegetable tannin. From the 1850s to the 1920s cheaper catechol (no longer vegetable oil, but chemicals) tanned leathers began to be produced which resulted in the problem of red rot.

Traditional tanning follows these steps: limed and dehaired, delimed, drenched in bran and citric acid, placed in a vat with tannin in it while progressively upping the strength of the tannin, dried, split and then finished. Modern methods of tanning are less time consuming. They involve stronger liquor (chemical in the vat), mechanical action to speed tanning, pH control, and a precise control of acids and salts.

Tanning is subdivided into vegetable tanned (used in historical and traditional work) and chemical tanned (often called chrome tanned and used in clothing), and then combination tanned (provides the flexibility of vegetable tanning and the longevity of chemical). The objective of tanning is to render the hides and skins resistant to decomposition or bacterial decay and to provide it with tensile strength, flexibility and abrasion resistance.

As for vellum and parchment, it is a semantic nightmare. The meaning of the word can vary with country origin, language, period in which the term was used, the animal it comes from, the usage to which it is being put, or a combination of any of those! In the European continent, the term parchment, according to Dan, is used as a generic term for any skin processed in a manner for binding. Whereas the term vellum, which comes from old French, may indicate thin material finished on both sides and used for writing.

In England specifically though, vellum refers to skin that is finished on one side only and used for binding, and parchment is finished on both sides and used for writing.

Both vellum and parchment are made by stretching skin and scraping it over and over again. Vellum is very stable: it’s almost a neutral pH level. Often times the term “limp vellum bindings” is heard and this refers to an old form of binding used to make the cheap “paperbacks” of medieval times – it’s very durable though!

It does caulk easily with water, so relative humidity effects it a lot.

Example of limp vellum bindings (image credit: andrewhuot.com)

This was just the beginning of information we received at the workshop. We also covered what makes leather quality good, how to tell goat skin from pig or calf, and what type of leather is good for bookbinding. It was a very informative workshop and provided a good introduction to leather and to leather-working as we also covered paring knives and how to pare the leather.

Guest blogger Arielle VanderSchans is a linguist and librarian living in Canada. She currently studies bookbinding through the Canadian Bookbinding and Book Arts Guild. You can follow her as she learns the trade here: https://ariellesbindery.com