Tatum Pin Perforator, American

In 1855, spurred by Great Britain’s adoption of perforated stamps, Postmaster General James Campbell ordered the US Postal Service to adopt perforation for all US stamps. (1) Perforated stamps had advantages: they did not require the time and attention it took to cut stamps with scissors from the sheets on which they were printed, and they prevented loss from careless tearing. That same year, Toppan, Carpenter, Casilear & Co., who had been engraving and printing US stamps since 1851, bought its first perforating machine from its English inventors, Henry and William Bemrose. Two years later, in 1857, the United States sold its first perforated stamps, coincidentally introducing the public to the convenience of perforated paper.

Businessmen like Samuel Tatum were quick to see the possibilities of perforating paper for purposes other than the separation of stamps. Toward the end of the century, Tatum had retooled his foundry and factory in Cincinnati to cast metal parts for manufacturing the paper perforators that had become essential equipment in stationery binderies. Stationery binders, who supplied their customers with ledgers for recordkeeping and other paper for commercial transactions, were in the market for perforating machines that would allow them to provide their customers with more profitable products and services. It did not take long before stationery binders were offering their customers the option of perforating checkbooks, receipt books, coupons, tickets, calendars, notepads, and other paper to be separated before discarding, forwarding, or saving. Perforating also came into use to cancel checks and other documents.

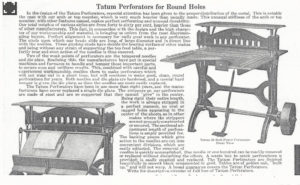

In 1912, Tatum explained in a catalog of printing machinery why the pin perforator he manufactured was superior to others. (2) The special attention given to the weight of the metal parts accounted for the machine’s durability and precision. The top piece was made exceptionally heavy to ensure that the stacks of paper fed under it were held securely in place between the perforating needles above and the die below. Flawless alignment of parts guaranteed true and even action of the needles to repeatedly and uniformly punch perfectly round holes. The design of the perforator also allowed for adjusting placement of the needles for custom work. Sections of needles could be removed or replaced without disturbing other sections. The perforator could be ordered either motorized or with a treadle. An ordinary or an automatic feed gauge could be included with either. All pin perforators were sold with a waste box to catch the punches.

In 1912, Tatum explained in a catalog of printing machinery why the pin perforator he manufactured was superior to others. (2) The special attention given to the weight of the metal parts accounted for the machine’s durability and precision. The top piece was made exceptionally heavy to ensure that the stacks of paper fed under it were held securely in place between the perforating needles above and the die below. Flawless alignment of parts guaranteed true and even action of the needles to repeatedly and uniformly punch perfectly round holes. The design of the perforator also allowed for adjusting placement of the needles for custom work. Sections of needles could be removed or replaced without disturbing other sections. The perforator could be ordered either motorized or with a treadle. An ordinary or an automatic feed gauge could be included with either. All pin perforators were sold with a waste box to catch the punches.

In its advertising, the Tatum Company emphasized that the special care taken in casting, tempering, and hardening its perforator’s die plate and needles ensured its machine’s incomparable performance. Tatum claimed no die plate forged in his Cincinnati foundry had ever required replacement in over a decade of use. The perforator was beautifully finished in smooth black and ornamented in gold. The table on which the paper was stacked was made of golden oak that would not warp. The Tatum Company guaranteed its perforator with pride.

1)The Smithsonian Museum’s National Postal Museum tells the story on its website of how US postage stamps came to be perforated and lists publications for further reading. See here.

2)The Tatum perforator shown here was the gift of Klaus Rotzscher. It was in use for many years in his Pettingell Bindery in Berkeley, California.