Gutenberg invented the printing press about 1450 in Germany. Although a technological revolution by all counts, it hardly spread like wild fire, even in Europe. The manuscript tradition continued strong for many decades.

In the island territory known as Iceland, the advent of printing was even slower than in most places. The first press arrived in the country about 1530, nearly a century after Gutenberg’s breakthrough. That press, likely built in Sweden, was put to use by the Catholic bishop of North Iceland, at a place called Hólar, printing religious tracts and a few of the Icelandic sagas.

The Bishop Printer

A half century later, another bishop — now of the Lutheran Church — had the old press repaired (or perhaps replaced), sent his printer to Copenhagen for supplies and training, and embarked on a big project: printing the Bible in Icelandic.

Bishop Guðbrandur Þorláksson (1541 – 1627) had his work cut out for him. He had to translate the good book into the vernacular (Icelandic, also called Norse), augment his supply of moveable type, obtain paper and appropriate woodcuts with which to illustrate the 600 plus page work, and – perhaps most difficult of all – raise the funds to pay for it all. In the last task, he was assisted by a mandate from the King of Denmark, the ruler of Iceland, that each church in Iceland purchase one copy of the finished book. The cost was set at nine rix dollars, the value of three cows, although a number of sources say that reduced prices were offered to parishes in straitened circumstances.

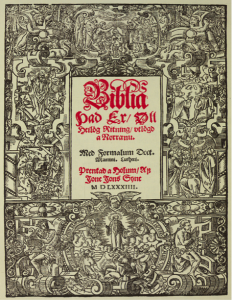

In his magnum opus, Bishop Þorláksson was aided by his printer, Jón Jónsson, whose name appears on the frontispiece of what is commonly called Gudbrand’s Bible. However, it is said that the good Bishop himself took a turn at printing and may even have cut some woodcuts himself.

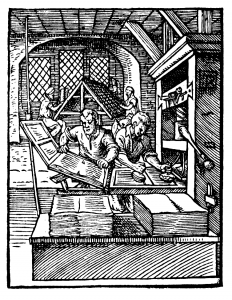

Engraving of a wooden printing press of 1568. The print shop at Hólar may well have looked something like this. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

The Traveler

More than 200 years after the publication of the Icelandic Bible, a Scotsman, the Reverend Ebenezer Henderson, wrote about his travels to Iceland in the early 19th century. As a member of Bible propagation society, Henderson has a vested interest in all things biblical. He was most interested in the bishop and his print works:

[He] rendered [the press] more complete by the addition of various implements which he had partly obtained from abroad and partly constructed by his own ingenuity and labour; for being a great mechanic, he could imitate almost anything he saw, or which he heard described by others. This aptitude was of great service to him, as it enabled him in no small degree, to accelerate and beautify his typographical productions.

Henderson claims to have seen the bishop’s diary with a full account of the Bible project:

From this MS it appears that he gave away a considerable number of copies gratis; to some parishes ten, to others twenty, accompanying them with the pious wish that they might advance the best interests of the receivers.

Five hundred copies of Gudbrand’s Bible were printed; only a few remain accounted for, including one on display at Iceland’s National Museum in Reykjavik and one in the collection of St. John’s College in Cambridge, England. In 1984 Iceland issued a stamp honoring the 400th anniversary of this landmark in national literature.

Frontispiece of Gudbrand’s Bible. Above the date it reads in Icelandic “Printed at Hólar by Jón Jónsson.” At The National Museum of Iceland one may listen to an audiotape of “Jón Jónsson” and his daughter detailing their lives in service to the bishopric.

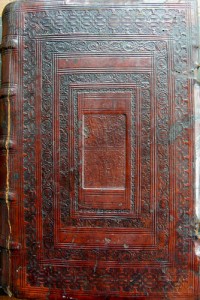

Calfskin cover, with blind-stamping, for Gudbrand’s Bible in the collection of St. John’s College, Cambridge. This expensive binding would not have been common to all 500 Bibles printed; it is not known with certainty whether the binding was done in Iceland or perhaps in Germany or Denmark. The traveler Ebenezer Henderson wrote that “one hundred were sent to Hamburgh to be bound, and a bookbinder was brought from that city in order to bind the remainder.” Image from St. John’s College Library.

The Island Printshop

Mirabile dictu, the episcopal press remained the only print shop in Iceland for over 200 years! And, it seems, the same printing press that printed Gudbrand’s Bible can be credited with all locally printed literature during that period!

It was not until 1772 that a man who called himself Olavius received permission from the Danish king to open an independent print shop in Iceland. The next year Olavius arrived at Stykkishólmur, a small community on Iceland’s west coast with a printing press in tow. With financial support from a wealthy farmer he moved the press into a house on a small island called Hrappsey. Legend has it that the dwelling was haunted by a man who had hanged himself in it. Apparently the ghost remained in the structure even when it was moved from one place to another.

For over 20 years Olavius and others printed a number of books and pamphlets in both Danish and Icelandic. The Hrappsey Press is credited with producing the first Icelandic periodical, a publication in Danish called Icelandic Monthly News (Islandske Maaneds-Tidener), which was available by subscription.

In the last year of the 18th century the episcopal press at Hólar was closed down and the 19th century began with a purely secular print industry in Iceland.

Islands in the fjord visible from Stykkishólmur. The island Hrappsey, which never had more than a couple of dozen inhabitants, is now unoccupied. Photo, Eleanor Boba.

— Eleanor Boba

Sources:

Henderson, Ebenezer. Iceland, or the Journal of Residence in that Island, 1818. Accessed via Google Play, September 2014.

Hermannson, Halldar. Icelandic Books of the Sixteenth Century, Islandica, Vol. IX. Ithaca: Cornell University Library, 1916. Accessed via Google Play, September 2014.

___________________. Literature of Iceland Down to the Year 1874, Islandica, Vol. XI. Ithaca: Cornell University Library, 1918. Accessed via Google Play, September 2014

Making of a Nation: Guide Book of the National Museum of Iceland’s Permanent Exhibition. Reykjavik: National Museum of Iceland, 2011.

Website: Island Hrappsey. http://nat.is/travelguideeng/island_hrappsey.htm. Accessed September 2014.