Smyth #3 Book-Sewing Machine, American ca. 1880

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, as the Industrial Revolution spread across Europe and the United States. bookbinders began to rely more and more on machines that could replace handwork. By 1850, commercial binderies were already depending on machines to shape the text block (sewn, or printed pages) before it was fitted into the case, or cover. Cases were quickly and uniformly decorated by embossing presses, and instead of workers who beat the text blocks flat, machines called smashers did the job. Sewing was one of the last binding tasks to be mechanized.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, as the Industrial Revolution spread across Europe and the United States. bookbinders began to rely more and more on machines that could replace handwork. By 1850, commercial binderies were already depending on machines to shape the text block (sewn, or printed pages) before it was fitted into the case, or cover. Cases were quickly and uniformly decorated by embossing presses, and instead of workers who beat the text blocks flat, machines called smashers did the job. Sewing was one of the last binding tasks to be mechanized.

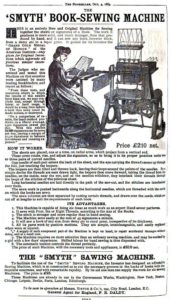

By the 1860s, Irish American inventor David McConnell Smyth had turned his attention from creating machines that could sew cloth or shoes to machines that could sew books. In 1868, he patented his first book-sewing machine. Improvements followed. Smyth’s innovation was to abandon straight needles for curved needles that could sew each signature to the one that came before it. An operator would place a signature on one of the machine’s rotating arms. When the rotating arm turned, it would raise and deliver the signature to needles that would secure it with thread into its place in the text block. Smyth ensured the success of his No. 3, put on the market in 1886, by adding to it a mechanism to stab holes in the spines of the signatures for the needles to pass through. Before this innovation those holes were put in by an operator at a saw machine, and too often produced irregular or too-deep cuts in the signatures that ruined the spine of the book.

Smyth’s book-sewer was met with acclaim. In 1879, the American Institute of the City of New York, founded in 1828 to promote domestic industry, awarded Smyth a gold medal for it, judging his invention to be “so important in its use or application as virtually to supplant every article or process previously used.” The No. 3 brought about a revolution in bookbinding. “Smyth sewn” became a term of art that referred to a method of sewing together folded, gathered, and collated signatures with a single thread sewn through each signature’s fold. The No. 3 greatly increased book production and at the same time transformed the bindery. In the hands of a trained operator, the No. 3 could sew three thousand signatures an hour that were of better quality than hand-sewn signatures; in practical terms, one No. 3 could replace ten booksewers on the factory floor.

Smyth’s book-sewer was met with acclaim. In 1879, the American Institute of the City of New York, founded in 1828 to promote domestic industry, awarded Smyth a gold medal for it, judging his invention to be “so important in its use or application as virtually to supplant every article or process previously used.” The No. 3 brought about a revolution in bookbinding. “Smyth sewn” became a term of art that referred to a method of sewing together folded, gathered, and collated signatures with a single thread sewn through each signature’s fold. The No. 3 greatly increased book production and at the same time transformed the bindery. In the hands of a trained operator, the No. 3 could sew three thousand signatures an hour that were of better quality than hand-sewn signatures; in practical terms, one No. 3 could replace ten booksewers on the factory floor.

The Smyth Manufacturing Company of Hartford, Connecticut, is still in business today manufacturing and selling bindery equipment, but it sold its last curved-needle sewer in 1928. Bookbinding took another direction in 1935 with readers’ preference for inexpensive perfect bound paperback books, first published by Albatross Books in Germany, Penguin Books in England, and Pocket Books in the United States. Perfect binding requires no sewing. Cover and pages are glued together at the spine; the book’s edges are then trimmed “perfectly” to size.

The Smyth No. 3 seen here is one of only a handful known to exist.

1)Smyth’s 1868 patent, no. 74,948, can be seen here.

2)Smyth’s 1879 patent, no. 220,312, can be seen here.

3)The Smyth No. 3 in this collection was bought at auction.