A library in Raleigh, North Carolina, displays the result of its book repair work in “before” and “after” book carts. State Library of North Carolina, public domain.

“A WPA book repair project working through the summer vacation period has reclaimed 210,438 books from the school junk heap and made them clean and fit for use.” (New York Times, 1938).

The New Deal agency Works Progress Administration (later renamed Work Projects Administration) lasted only about eight years, from 1935 to1943, during the height of the Great Depression, but had an outsized influence. The goal of the program was to provide relief through employment while, at the same time, making lasting improvements to the country’s infrastructure and cultural landscape. Much has been written about WPA construction and art projects, less about the WPA-funded writing, theater, museum, and music projects, and little about the library services program.

While not as visible as some of the projects mentioned above, libraries benefitted from the federal largesse in many ways – the creation of small rural libraries and community reading rooms, cataloging projects, and bookmobiles made reading material available to a much larger share of the population. In rural, mountainous Kentucky, books and magazines were carried by women on horses and mules – the so-called pack-horse libraries. All told, library projects were set up in 45 states (out of 48).

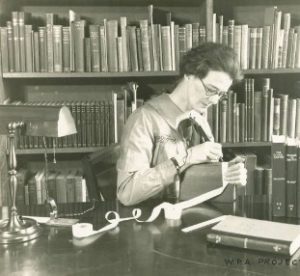

A woman uses a stylus to engrave a title on a new book binding at the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore. Public domain.

Bookbinding and book repair were significant, if particularly quiet (as behooves library projects) parts of the program. Often relegated to back rooms and library basements, this quickly taught work gave employment to thousands of individuals, mostly women, during a time of economic hardship. All told, 94,700,000 books and periodicals were repaired over eight years, according to the final report of the WPA. Another ten million were repaired or rebound by teens working under the National Youth Administration, both boys and girls.

Like other WPA programs, funding for book repair projects worked something like matching grants: the Feds paid for wages and some project costs, while the local jurisdiction picked up the tab for most supplies and equipment.

Drilling down

WPA book repairers utilized a number of methods meant to return the books to service quickly, but without regard to the book’s long-term health. These methods included simple mending of torn pages, drilling holes using awls and sewing through the pages of books where the binding had completely fallen apart, cleaning soiled covers and pages, regluing pages to book spines, inserting typewritten pages where originals were missing, and rehousing volumes with conservation materials where covers were beyond repair. Sometimes they applied shellac to the edges of the printed pages as a preservative. In the case of school textbooks, most of which were in terrible condition, workers might cannibalize some copies in order to create complete books. A few sites worked repairing books in braille.

In the early days, the repair of school textbooks was touted as a cost-saving way to insure an adequate supply for classrooms. A no-brainer, one might say. Unfortunately, that aspect of the program ran afoul of lobbying by book publishers who claimed that the re-use of older textbooks was a detriment to learning. Surely, they had economics at top of mind. In any case, in the last four years of the WPA the repair of textbooks was suspended.

Books for all?

African American workers mending books in the “colored section” of the WPA Bookbinding Project, New Orleans. Public Domain.

In many parts of the United States, particularly the deep South, racial segregation remained the way of life in the 1930s and 40s, with libraries no exception. WPA administrators felt forced to comply with both de jure and de facto segregation. Where African Americans were hired to do book repair, they served in “colored sections.” Even bookmobiles, one of the most successful initiatives of the library services program, were divided by route and content according to white or black population centers.

A project shelved

WPA library services, like other New Deal programs, wound down as the war in Europe wound up. By 1943, federal resources that had gone toward library projects were repurposed for war work, including the dissemination of information to the public on civil defense, such as air raid manuals. Some book repair work continued at military bases alongside cataloging and general library organizing.

WPA library services, like other New Deal programs, wound down as the war in Europe wound up. By 1943, federal resources that had gone toward library projects were repurposed for war work, including the dissemination of information to the public on civil defense, such as air raid manuals. Some book repair work continued at military bases alongside cataloging and general library organizing.

Nonetheless, the WPA bookbinding and repair work made a lasting contribution. Many of the reclaimed works can still be found on library and school bookshelves. For the women and youth who had been employed by the program, new jobs opened up in defense industries or the military. A few ex-WPA workers were able to translate their new skills to permanent library work.

–Eleanor Boba

_____

Sources for this post include The Final Report on the WPA Program, 1935-43 and The Final Report on the National Youth Administration, 1936-1943, both accessed via The Library of Congress website; and Nick Taylor, American Made: The Enduring Legacy of the WPA, 2008.