Our unique collection of 19th and early 20th century booking binding equipment is the cornerstone of our permanent exhibit. Preview some of these rare objects now. Please contact our collections team for more information.

Board Shear, American

When case binding became the norm for edition binding in the 1830s, binders sought an easier way to trim cover board. These boards, made of layered waste paper or paper pulp sandwiched between two sheets of paper under high pressure, is difficult to trim by hand. The fibers in the paper can shred, or the cut go askew. In an industry increasingly concerned with the ability to create identical books with cases made with bookboard and the less-forgiving fabric that covered it, a clean, clear cut was essential. The Board Shear, able to produce precise and clean cuts, became an essential tool.

When case binding became the norm for edition binding in the 1830s, binders sought an easier way to trim cover board. These boards, made of layered waste paper or paper pulp sandwiched between two sheets of paper under high pressure, is difficult to trim by hand. The fibers in the paper can shred, or the cut go askew. In an industry increasingly concerned with the ability to create identical books with cases made with bookboard and the less-forgiving fabric that covered it, a clean, clear cut was essential. The Board Shear, able to produce precise and clean cuts, became an essential tool.

Hickok Pen Ruling Machine, American 1901

Stationery binders would usually rule the blank books they produced, inking in horizontal lines to write on and vertical lines to write between, a practice that goes back to the Middle Ages. When ruling was done by hand using cylindrical rulers and dip pens, the time that went into ruling an account book must have been the largest single component in its price. Early in the 19th century the pen-ruling machine was invented; this reduced the cost of wages for ruling but also became the greatest capital expense in the stationery binder’s shop. This change is reflected in the American directories of the later 19th century, which used the term “blank book manufacturers” for what the English continued to call vellum binders.

Stationery binders would usually rule the blank books they produced, inking in horizontal lines to write on and vertical lines to write between, a practice that goes back to the Middle Ages. When ruling was done by hand using cylindrical rulers and dip pens, the time that went into ruling an account book must have been the largest single component in its price. Early in the 19th century the pen-ruling machine was invented; this reduced the cost of wages for ruling but also became the greatest capital expense in the stationery binder’s shop. This change is reflected in the American directories of the later 19th century, which used the term “blank book manufacturers” for what the English continued to call vellum binders.

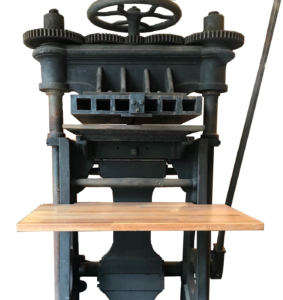

Imperial Arming and Printing Press, English ca 1880s

Called arming presses or blocking presses in England and embossing machines or stamping presses in America, these machines used heating irons to heat up a chase, and then a lever arrangement would bring it down and impress a design, often in gold, on to the book cover or spine. Our machine, a rarity which could both print and emboss, was only produced at the end of the 19th century, and may have been obsolete by the time it was manufactured.

Called arming presses or blocking presses in England and embossing machines or stamping presses in America, these machines used heating irons to heat up a chase, and then a lever arrangement would bring it down and impress a design, often in gold, on to the book cover or spine. Our machine, a rarity which could both print and emboss, was only produced at the end of the 19th century, and may have been obsolete by the time it was manufactured.

Lying Press and Plough, American 20th Century

Before mechanization, the lying press was the binder’s all-purpose mainstay piece of equipment, used for backing books, pressing textblocks, gilding edges, and, with its accessory the plough, for trimming the edges of books, cutting coverboard, and cutting reams of paper to size. The design was developed sometime in the fifteenth century, was refined in the eighteenth century, and has remained largely unchanged (and in use by many hand-binders) to the present day.

Palmer & Rey Guillotine, American ca. 1880s

For centuries, trimming the edge of a text block required use of a chisel or a plough, a specialized plane passed over the papers’ edge, shaving off a millimeter at a time. With three edges to trim, this took time: a binder doing multiple books spent a lot of time shaving text blocks to a uniform trim and smoothness.

The introduction of the guillotine in the 1820s made trimming fast and uniform. A block of paper was tightly clamped so that a blade could cut through cleanly it as it might through a block of wood. The improvement in consistency and speed was enormous.

Sanborn Embossing Press, American ca. 1884

In 1884, Geo. H. Sanborn & Sons published a catalog of its bindery equipment, which included its No. 5 Embossing Press, described as a longtime favorite in the industry and recommended for general work. Embossing presses like the No. 5 had been standard equipment in binderies since the 1830s because they produced enough heat and pressure to work with the cloth-covered board cases, and eliminated the handwork once required when covers were custom made for each book. ABM’s Sanborn embossing press, an imposing 7 feet tall, greets visitors at the entry to the museum.

Singer Book-Sewing Machine, Model 6-9, American ca. 1911

ABM’s Singer Model 6-9, ca. 1911, meant for industrial use, was purpose-built and advertised specifically for sewing through paper–as much as 3/4 of an inch. The machine could be operated by foot treadle or–later–by electric motor. Singer advertised an accessory folder that attached to the sewing table: a folded signature was sewn in the machine then slid into a hopper where it was folded by dropping through two rollers.

Smyth #3 Book-Sewing Machine, American, ca. 1880s

By the 1860s, Irish American inventor David McConnell Smyth had turned his attention from creating machines that could sew cloth or shoes to machines that could sew books. In 1868, he patented his first book-sewing machine. Improvements followed. Smyth’s innovation was to abandon straight needles for curved needles that could sew each signature to the one that came before it. An operator would place a signature on one of the machine’s rotating arms. When the rotating arm turned, it would raise and deliver the signature to needles that would secure it with thread into its place in the text block. Smyth ensured the success of his No. 3, put on the market in 1886, by adding to it a mechanism to stab holes in the spines of the signatures for the needles to pass through.

C. Starr Roller Backing Machine, American, ca. 1856

As the structure of the book changed from single-folded folio to multiple signatures sewn together at the spine, bookbinders had to deal with swell, the thickness that accumulates at the spine in a stack of folded and sewn signatures. Swell can create a spine that is wider than the text block, make it difficult to open the bound book, or cause the spine to buckle. To avoid this, binders accommodate the swell from paper and thread by rounding the spine. To round manually, the binder uses light blows from a rounding hammer to push the outer edges of the spine down, creating a spine with a rounded shape. This forces the fore edge into a concave shape. This takes time–time saved with the advent of roller-backing machines.

Tatum Pin Perforator, American

In 1855, spurred by Great Britain’s adoption of perforated stamps, Postmaster General James Campbell ordered the US Postal Service to adopt perforation for all US stamps. Perforated stamps had advantages: they did not require the time and attention it took to cut stamps with scissors from the sheets on which they were printed. That same year, Toppan, Carpenter, Casilear & Co., who had been engraving and printing US stamps since 1851, bought its first perforating machine. Two years later, in 1857, the United States sold its first perforated stamps, coincidentally introducing the public to the convenience of perforated paper.

In 1855, spurred by Great Britain’s adoption of perforated stamps, Postmaster General James Campbell ordered the US Postal Service to adopt perforation for all US stamps. Perforated stamps had advantages: they did not require the time and attention it took to cut stamps with scissors from the sheets on which they were printed. That same year, Toppan, Carpenter, Casilear & Co., who had been engraving and printing US stamps since 1851, bought its first perforating machine. Two years later, in 1857, the United States sold its first perforated stamps, coincidentally introducing the public to the convenience of perforated paper.

For more information about our collection, or to request access to items in our collection, please fill out the form below.