Have you ever wondered what advice to give young people about to get married? In the second half of the sixteenth century, the book market abounded with guidebooks about how to live – how to travel, how to write about travel, how to be a prince, how to be a good father – and even how to die. There was a whole genre of books that gave advice to newlyweds, called in German “Ehespiegel,” or marriage-mirrors. Their purpose was to hold a mirror up to marriage, tell young people what married life was really like, and help them make good decisions.

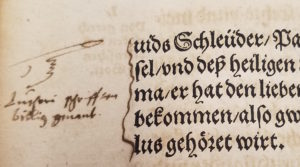

The oldest book in the collection of the Bookbinders Museum is actually four books that were collected and sewn together, including an Ehespiegel written by the religious reformer Cyriacus Spangenberg. In 1568, an unknown reader took two partial copies of the Spangenberg Ehespiegel – it appears that they did not have a complete copy of either the 1561 or 1562 edition, so they combined parts from both – and added in some commentaries on St. Paul’s Letters to the Corinthians and a history of Corinth, all written by the same author. They bound the works together in a highly ornate leather binding, stamped with figures of saints.

The Ehespiegel was clearly intended to be a useful book. Comprised of seventy sermons preached by Spangenberg to brides and grooms, the volume has a table of contents organized by topic and another table of contents organized by the Biblical text used for the sermon. And this volume of the Ehespiegel was well used. Throughout the book, an unknown early modern reader wrote comments in the margins, including drawings of hands to point to passages that were particularly important.

The advice given by the Ehespiegel was both moral and practical for the newlyweds, and tells the modern historian much about marriage customs at the time. To judge from Spangenberg, early modern weddings could be quite the affair. In his sermons, he criticizes the excessive eating and drinking at wedding feasts and bemoans the exorbitant cost of many celebrations. He expresses concern about the singing and dancing that took place after the meal, and tells a story about a pastor who played the fiddle himself for a wedding dance and whose hand was struck by lightning as punishment. Through Spangenberg’s criticisms of the conduct of wedding guests, we get an image of the raucous celebrations that must have taken place around him.

Perhaps we would not be interested in following Spangenberg’s prescriptions for successful marriages. Certainly his figure of the good wife as obedient and submissive is one that I am glad has been updated. However, texts like these Ehespiegel give us valuable insights into life in the past, insights both into what pastors like Spangenberg wanted life to be like and insights into how life was actually lived.

Guest blogger Laura Lisy-Wagner is an associate professor of Early Modern and Reformation History at San Francisco State University and author of the book Islam, Christianity, and the Making of Czech Identity, 1453 – 1683.