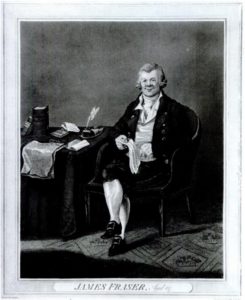

From Bookbinding in the British Isles. Fraser holds a paper titled “Plan for Reconciling the difference between the Masters & Journeymen Bookbinders.”

In 1740, when James Fraser (seen left) was born, the route to being a master bookbinder was clear, if not necessarily easy. Start in your mid-teens as an apprentice, survive apprenticeship and receive your journeyman papers, and finally–with luck–become a master. Apprenticeship, during which time a youth was trained (and educated), and worked for the master without payment, generally lasted 7 to 9 years. Once the worker reached journeyman status he worked for others, for wages, growing in skill until he was able to provide proof of his technical competence: his masterpiece. Once he had risen to the guild status of Master he could take on apprentices of his own, set up his own business, employ journeymen binders. Not every journeyman would become a master–some hadn’t the ambition, others never progressed to that level of skill.

But by the end of the 18th century, the ground rules were changing. The trade model was shifting to an employer-employee model, the journey from journeyman to master became harder to make, and relations between the two often became adversarial. Their goals were fundamentally different, and in the clash of man and master the seeds of trade unionism were sown.

We tend to think of unions as being a phenomenon of the 19th century, but the movement began far earlier than that. Starting in 1770, groups of journeyman bookbinders took to meeting at the Wheatsheaf Public House, just off the Strand in London. Like many guild groups, binders had long been in the habit of getting together after work to drink, talk shop, and carouse. But the men at the Wheatsheaf gradually talked more and caroused less. By 1779 they were calling themselves the “United Friends,” the first bookbinding trade society. This in and of itself was daring: trade unions, or “combinations”, were illegal.

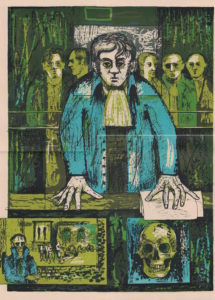

Less than a decade later, when the Friends got together to negotiate for a one-hour reduction in the work week–from 75 to 74 hours– the result was that most of the journeyman binders of London were laid off, and legal proceedings were started against them. Twenty-four binders were arrested and, while they were later released on bail, they were ordered back to work by the Judge, at the same hours and wages as before, and warned that if they did not comply, the leaders from each shop would be jailed. Some journeymen moved away from London entirely. Some complied with the judicial order. And some felt that it was time to make a stand. Six of the original twenty-four were sentenced to two years at Newgate Prison.

Cover by Rigby Graham for “One Hour Less”, by Trevor Hickman

Among these six was William Wood, a finisher who had just set up his own shop at the time when the strike began. The man who gave evidence against him, James Matthews, was Wood’s uncle-by-marriage, and testified reluctantly–perhaps because, even beyond the family connection, by the time of the trial, Wood was now on the Employer side of the equation.

Prison in the 1780s was as comfortable as a prisoner could afford to make it: for a price one might have a room to oneself, better food, and lighter, more comfortable shackles. The binders of London supported the five imprisoned men (the others were Thomas Armstrong, William Craig, Thomas Fairbairn, and Patrick Lilburne) to the tune of a guinea a week, and many of them visited–and drank heavily (Newgate, lacking in other comforts, had a tap room on premises). William Wood, less given to drink than his colleagues, was eventually ostracized for his disapproval, which may have been part of why his health deteriorated precipitously. He caught ‘gaol fever’ (typhus) and died.

The support Wood had lacked in life, he achieved in death. His funeral procession was well attended, and stopped at the home of his last employer, where the mistress of the house broke down in tears. The procession went onward to the Wesleyan Chapel in Tottenham Court Road, and after a short service Wood was buried.

His fellow binders in Newgate were released with a pardon from George III in June of 1788. They immediately gathered at a pub, the Cheshire Cheese, in Surrey Street, to celebrate with their supporters–who included, at this point, their employers, who had had to deal with the resentment of their employees over the fate of the “Martyrs”. The men were reinstated in their jobs, and for many years afterward a “Martyr’s Dinner” was held annually to celebrate the release of the four remaining binders.

The relations between man and master, and employed and employer, were still rocky. It was not until 1825 that the “Combination Laws,” which outlawed trade unions, were repealed. Gradually unionism spread throughout England, and in 1835 (half a century after William Wood’s death) the first national union of bookbinders was formed in Manchester. But not all the Martyrs continued to believe in the cause for which they had been imprisoned: by 1806, during the strike for the “Tea Half-Hour,” Armstrong and Fairburn, masters themselves, were strongly on the opposing side.

Click to read a song tea strikers penned about their need for tea: The Time We Have to Tea

What’s the connection between the master (James Fraser) and man (William Wood)? Fraser was one of the “Prosecuting Masters: in the One-Hour combination trial; he later appeared to regret his role, making statements that tried to justify the masters’ part in the dispute, and saying “A PROSECUTING, but I hope I shall never be a PERSECUTING MASTER BOOK-BINDER.”

What William Woods might have said in rebuttal, we shall never know.

______________________________________________

http://www.britannica.com/topic/organized-labor#ref540091

Bookbinding in the British Isles: Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century, Part 1, London: Maggs Bros. Ltd, 1996, page 86.

Hickman, Thomas: “One Hour Less: A Bookbinder Dies from Gaol Fever”. Wymondham: Brewhouse Private Press, Broadsheet Number 5, 1968.