The Guild of Women Binders and The Bindings of To-morrow

In an age largely given over to utilitarianism it is gratifying to find purposes and persons at variance with the conditions around them, and in no field is the discovery more productive of satisfaction that that of industry.[1]

Women have been closely associated with the needle arts for time immemorial. They are also closely associated with the hand sewing of books, but their role in the design and production of books beyond the hand binding era is more uncertain. However, it is indisputable that one of the pinnacles of early 20th century decorative bookbinding is the corpus of work produced by the Guild of Women Binders. These women provided some of the most technically adept and unique designs of the era by combining stylistic contemporary designs with sensitive color work.

The Guild of Women Binders was founded by Frank Karslake, a London bookseller and also founder of the Hampstead Bindery. Karslake was a bit of a rogue, who dabbled in multiple professions ranging from acting to ranch management, before trying his hand at bookselling and bookbinding. His interest in women binders emerged from his admiration of bindings exhibited at the Victorian Era Exhibition in 1897. Soon after seeing these examples, he invited several of the women binders to exhibit in his shop. This exhibit, Exhibition of Artistic Bookbinding by Women, confirmed to Karslake that maybe women really could distinguish themselves in this industry. Perhaps he saw an opportunity to profit from the novelty of women binders, but soon after, Karslake acted as agent to prominent binders like Constance Karslake, Edith de Rheims, Florence de Rheims, Mrs. Macdonald, Helen Schofield, Frances Knight, and Lilian Overton (to name a few). In 1899, Karslake’s vision evolved into the workshop and business venture that became the Guild of Women Binders. Women involved in the guild were typically middle class and had a background in artistic education.

At the guild women received instruction in hand-bookbinding, and were offered employment after the completion of their training. Guild binders set a standard of merit and produced some of the most detailed work of the time. The guild not only extended the work of women into a field that allowed them to make a livable wage, but also encouraged women to express themselves artistically.

In establishing both the Guild of Women Binders and the Hampstead Bindery, Karslake ventured to establish a system that would both train and employ women binders. He boasted that the fine, detailed bindings produced by his lady bookbinders were superior to those worked by men, and felt certain that the artistic work by women would distinguish his business from other booksellers. He bragged, “booksellers who most readily read the signs of the times will be the most prosperous members of the trade. One of such signs is the growing demand for really artistic bindings.”[2]

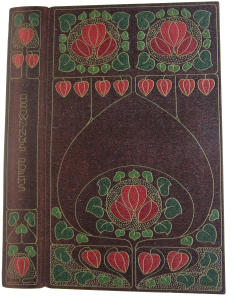

Browning’s Poems designed and worked by Miss Murial T. Driffield. Dark brown morocco, floral design, with 165 red and green inlays; gold-tooled brown morocco doublures; vellum fly-leaves, uncut, top edges gilt.

The intricate binding designs of the Guild women, were a direct result of their own creative design sensibilities. Additionally, the increased reliance on bookbinding machinery at the time created a niche for fine hand bound volumes. As Anstruther mentions in his introduction, “The introduction of machinery has nearly lost to use the self-reliant, consciously-proud figure of the English craftsman; the old Trade Guilds, with their dignified constitutions and worthy aims, had little in common with their corporate successors of to-day…”[3] He goes on to say, “the woman-binder first of all makes herself thoroughly acquainted with the mechanics of her calling, and that after this she is in a position to bring to bear the results of her education, her artistic training, and her decorative skill upon the cover which she herself has put upon the book.”[4]

When Karslake first conceived of the idea to compile a book, publishers refused it because books on bindings were said to be unprofitable. A warning which Karslake ignored when he published The Bindings of To-morrow himself in 1902, with the assistance of W. Griggs who printed an edition of 500 copies. This book provides a unique historical insight into the binding process and a glimpse into the under-represented work of women binders. A year after publication, Karslake was forced to offer the remaining 150 copies of the book to booksellers at a fraction of the original price.

A first glance through the plates in this volume, all of the illustrative of accomplished work, will convey a pleasurable sense of harmonious colouring and beauty of form. On closer examination they will be found abounding in richness of detail, in painstaking excellence of workmanship; the designs for the most part formed in what seems an almost infinite variety of graceful interlinear patterns. Still further scrutiny, taking the binding in relation to the character of the book that it enshrines, will bring out what is perhaps the most attractive quality of many of these bindings — a subtle harmony between the body and soul of the volume, which alone places the work beyond the domain of even the most exalted artisanship.[5]

From a historical perspective, the final product of The Bindings of To-morrow is a testament to the highly technical printing processes available at the time. The book includes fifty leaves of full page, full color plates. Likely these were chromo-lithographs, which were then foil-blocked with gold leaf, resulting in an impression to mirror the tooling on the original bindings. These processes were complex, and to see as many as fifty of these plates together in one volume is a truly beautiful rendering of the bindings. Any other reproductions would have paled in comparison to these as so much of the emotional reaction to these bindings comes through the color and texture of the decorations.

The American Bookbinders Museum has just acquired a copy of The Bindings of To-morrow, and we are thrilled to be able to share some pictures and commentary on the plates within.

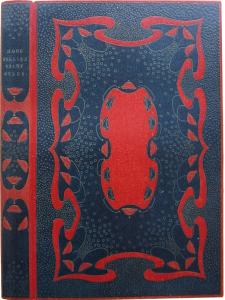

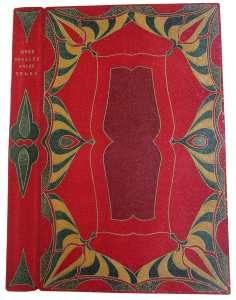

More English Fairy Tales designed and worked by Florence de Rheims, seen below, epitomized what Karslake considered to be the genteel and feminine touch found in the work of Guild binders.

More English Fairy Tales designed and worked by Miss Florence de Rheims. Red morocco, entirely covered with an inlay of dark blue morocco, with 74 flowers inlaid in red and blue.

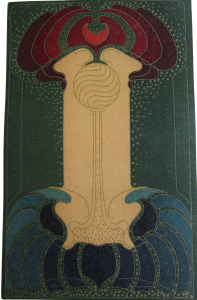

The example below, the authors’ favorite, creates a border of gold-tooled butterflies made up of red and green inlays. Helen Schofield’s artistic training prior to entering the guild is evident in the design.

More English Fairy Tales designed and executed by Miss Helen Schofield. Scarlet morocco, centre panels of dark red morocco, border design of conventionalised butterflies, in 198 green and yellow inlays.

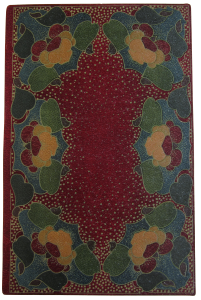

The binding, below, was adapted from a Moresque design and crafted by Florence de Rheims. Hundreds of pieces of colored leather make up the unconventional shamrock design. How fitting for a book of Celtic fairy tales.

More Celtic Fairy Tales adapted form a Moresque design and executed by Miss Florence de Rheims. Cobalt-blue morocco, inlaid design, consisting of 390 pieces of green, blue, red and yellow leather; blue morocco doublures, with elaborate shamrock design and 36 small coloured inlays.

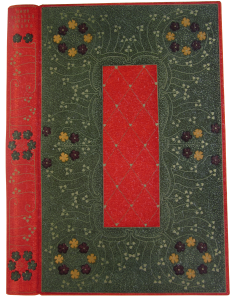

Another book of fairy tales designed and worked by Lilian Overton, blind-tooled and inlaid with flowers in purple, yellow, and green. Lilian combined the inlays and delicate tooling to create a manicured English garden theme.

More English Fairy Tales designed and worked by Miss Lilian Overton. Scarlet morocco, the sides covered with a dark grey inlay, and 102 inlaid blind-tooled flowers, in purple, yellow and green.

Indian Fairy Tales designed and executed by Miss Lilian Overton. Red morocco, inlaid floral design, consisting of 250 pieces of green, blue, red and yellow leather.

These examples demonstrate the striking style of Guild binders taking precedence over elaborate technical processes. To be sure, the intricacies of tooling and inlay work require great technical aptitude, but the lasting effect truly derives from the overall design.

Doublure from Keats Poems designed and worked by Miss Florence d Rheims. Green morocco doublure with 56 inlays in white, blue, crimson and scarlet.

Karslake had minimal experience in professional bookbinding. Though challenging to confirm, it seems his primary motivation in promoting the work of women in the field of bookbinding was simply for profit, rather than the advancement of women in the profession. Possibly through his own inexperience with the trade, or through his own carelessness, his venture was not successful in the end. Some bindings were suspected not to have been done entirely by the women of the Guild; professional binders of the time claimed the work too sophisticated for the hands of amateur woman and accused Karslake of passing off the work of Hampstead Bindery tradesmen as the women’s. Rumors circulated around Karslake’s dishonesty, and book buyers were wary.

The questionable bindings saturated the market, and many of the most detailed bindings, designed to match the artistically-printed pages, were not sold. Karslake’s business began to fail and some women binders no longer wanted to be associated with his practices. Sadly, the Guild closed its doors in 1904 and subsequently, poor Karslake went bankrupt. For the women who were involved with the Guild, their training and talent ended up tainted by the controversy surrounding Karslake. Some women continued working as binders independently after the dissolution of the Guild but some quit the whole business altogether. A sad ending to such a vibrant and talented group of women. However, despite this ending, their work remains, an inspirational manifestation of these women’s visions; a testament of creativity and individuality regardless of the role of men in the execution of the design of the bindings.

So few are the years dividing us from William Morris and his work…yet even now the Kelmscott books find an honoured place in the showcases of the British Museum. Is it too fond a thought which now opens up a similar prospect for some of the bookbindings, supposing the Guild were to end its existence to-morrow?[6]

–Co-written by Alex Post, volunteer and Amelia Grounds, Librarian.

Work Consulted

Tidcombe, M. (1996). Women Bookbinders: 1880-1920. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press.

Anstruther, G. Elliot. (1902). The Bindings of To-morrow. London

[1] Anstruther, vii.

[2] Tidcombe, 129.

[3] Anstruther, vii.

[4] ibid, xiii.

[5] ibid, ix.

[6] ibid, viii.