Samuel Mearne: Bookbinder and Copyright Enforcer

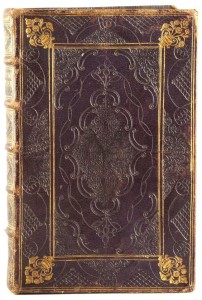

A cursory search for Samuel Mearne (1624-1683) reveals an English Restoration bookbinder and publisher associated with the cottage (or cottage-roof) style of binding, which is characterized by ornate and colorful covers, often with a floral theme.

Binding by Samuel Mearne. Author: Bacon, Francis, 1561-1626 Title: The essays or counsels, civil and moral, of Sir Frances Bacon. Published: London: Printed by M. Clark, for Samuel Mearne, 1680.

Samuel Mearne is recognized as one of the most notable pre-industrial English bookbinders, and also had a hand in hunting down illegal presses through his involvement with the Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers. Dig a bit further and you reveal an enterprising official who used England’s strict copyright laws to line his pockets and those of his friends.

Copyright in Early Modern England

In 1642, Robert Barker, formerly King’s Printer, wrote, “Printing is as inherent a Prerogative to the Crowne as Coining of Money.”* With this analogy, Barker insisted that it was the government’s job to distinguish the true from the counterfeit, which is great for currency but potentially dismal for free speech.

In 1529, almost 150 years before Samuel Mearne found his place in the Stationers’ Company, King Henry VIII sought to end printers’ and booksellers’ wanton disregard for copyright – though the modern term “copyright” is a misnomer. At this time, copyright as we understand it today did not exist; rather, governments issued licenses or privileges to individual printers for a certain span of time, and the documents were only enforceable in the territory of the issuing government.

Henry VIII (r.1509-1547), like other rulers of his day, drafted a list of forbidden books, many of which were religious texts that in some way disagreed with his vision for the newly-formed Church of England. He was succeeded first by his deeply Protestant, Catholic-hating son Edward VI (r.1547-1553), then later by his daughter, Mary I (r.1553-1558), an equally staunch Catholic who flipped around and banned Protestant material outright. The religio-political turmoil affected the printers and publishers as well as the audience they served.

While the earliest copyright privilege in England was issued in 1518 by the King’s Printer, Richard Pynson, it wasn’t until 1557 that a form of copyright law was codified with the establishment of the Stationers’ Company, which was given a monopoly on the print trade by Queen Mary in exchange for their help in preventing the production of seditious literature. England’s return to Protestantism under Elizabeth I (r.1558-1603) provided the comparative stability that allowed for the solidification of copyright privilege and permitted texts, and by the end of the Protectorate and the restoration of the Stuart monarchy under Charles II in 1660, a tradition of copyright and censorship was well-established.

Restoration Censorship

Enter Samuel Mearne. Around 1655, he journeyed to the Netherlands with some colleagues, where records indicate he probably worked for Charles II, who was residing there while in exile. After the Restoration, this loyalty led to Charles’s 1668 recommendation for Mearne to enter into the Stationers’ Company, beginning Mearne’s career as a censor – but with the standard petty bureaucratic corrupt twist. With his cohorts Thomas Sawbridge and Randall Taylor, Mearne prosecuted unlicensed publishers to the fullest extent of the law . . . when they happened to be people he didn’t like. In one instance, Mearne and his agents seized 1500 copies of A Treatise of Baptism from the nonconformist bookseller Francis Smith, also known as “Elephant” Smith. Smith’s publications were seen as dissenting and controversial, but that didn’t stop Mearne, Sawbridge, and Taylor from feigning compliance to the law and then printing and selling copies abroad, raking in a tidy profit. In contrast, one Roger L’Estrange, appointed as both the Surveyor of the Imprimery and Licenser of the Press, took his job incredibly seriously, going so far as to implant spies into the Stationers’ Company and even go undercover himself.

It is easy to be startled by Mearne’s hypocritical and self-serving behavior, but in truth, it is L’Estrange’s seemingly fanatical behavior that is more unusual. Samuel Mearne’s legacy brings up some interesting points about how history is written, or rather, what is frequently omitted. Large-scale corruption often results in scandal and juicy sections in history books, but small-scale corruption like Mearne’s easily fades into the mists of time.

Copyright in its modern form started taking shape in the reign of Queen Anne in the early eighteenth century – just in time, coincidentally, for the rise of the novel. One cannot help but wonder what Mearne would have thought of copyright law, had he lived to see it.

— Dorian Karahalios is a student at the Oregon College of Art and Craft, studying Book Art, and enjoys exploring the lesser-trodden paths of history.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

*Robertson, p. 3-4.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

References

Masters, Kristen. “Famous Figures in the History of Book Binding.” Books Tell You Why.com. 30

August 2014.

<http://blog.bookstellyouwhy.com/famous-figures-in-the-history-of-book-binding>

Robertson, Randy. Censorship and Conflict in Seventeenth-Century England: The Subtle Art of Division.

University Park: Penn State University Press. 2009.

“Timeline of the English Reformation.” Wikipedia.

<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_English_Reformation>

“Early British Copyright Law.” Wikipedia

<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_copyright_law#Early_British_copyright_law>

“Bookbinding.” Encyclopedia Brittanica Online.

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Bookbinding