I’ll confess as a kid I loved espionage: clandestine conversations, dark alley meetings, secret passageways. If it involved a high-level adventure… with a low-level of forgery… with maybe a secret handshake, I was in; and truth be told I still might be. Growing up pre-mobile phones and computers, note passing was the main form of communication throughout my education. I spent a lot of time on ciphers and codes and, of course, invisible ink because about 20-30 percent of all transmissions were intercepted by instructors. Looking back I am sure no one really cared what my youthful mind had to say, but I was sure that if caught I would be punished to the full extent of the elementary school penal code. So I stayed under the radar and wrote in my version of invisible ink: lemon juice applied with a toothpick. When the secret writing was heated writing would appear. Taking Meyer lemons off the tree in the backyard and running to my room to squeeze them into ink was particularly thrilling; yet again if caught probably nothing would have happened, though I pretended it would.

I recently read Prisoners, Lovers, and Spies: The Story of Invisible Ink from Herodotus to al-Qaeda and just as I suspected, invisible ink was not just about kids using toothpicks and lemon juice. It was the stuff of real cloak and dagger stories. But who invented invisible ink? Pliny the Elder, a Roman naturalist discovered that milk of the tithymalus plant (goats lettuce) written on a body, then dried, would produce letters when ashes were sprinkled upon it. Philo of Byzantium c. 280-220 B.C. in Alexandria advised the use of crushed gallnuts dissolved in water to write upon a body, and then the use of a sponge soaked in virrol (ferrous sulfate) rubbed gently over the writing to reveal the letters.

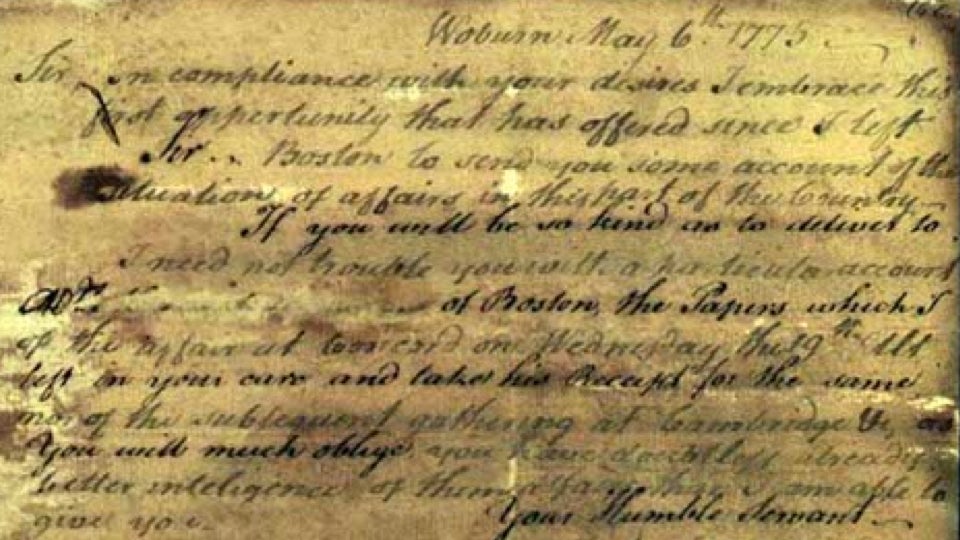

History isn’t at all murky when it comes to the wars fought and won by way of this secret writing. During the Revolutionary War invisible transmissions were written between the lines of letters and coded with an “F” for fire or an “A” for acid to clue the recipient in on what method to use to unveil the hidden ink.

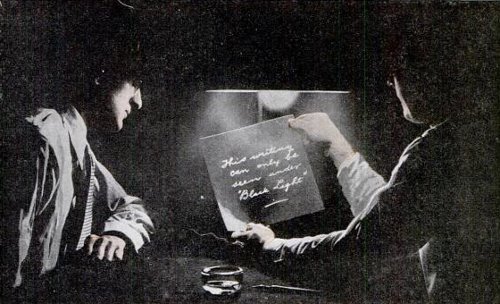

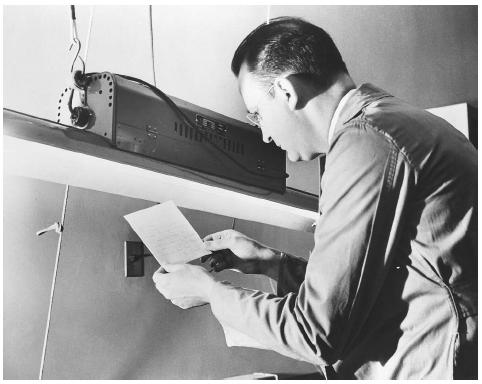

In 2011 the CIA released six World War 1-era documents dealing mostly with invisible ink. One formula containing starch has a recommendation of hiding the ink by ironing it in to a handkerchief, or the starch of a shirt collar, then soaking the article in water to release the ink for writing. These de-classified CIA documents can be viewed in their Electronic Reading Room by searching “secret writing”.

Another interesting story of clothing impregnated ink involves George Vaux Bacon, a Minnesota born spy working for the Germans in America. Bacon traveled to Rotterdam as an American journalist and began to send transmissions by writing between the lines of his reports using invisible ink he had smuggled, painted in the tops of his socks, then soaked in water to reveal the ink for writing.

The Geneva Convention brought fair treatment of war criminals and with it came the right for prisoners to write home. Captors were forbidden from tampering with the letters after they were written. The danger of prisoners revealing locations, work camp activities and information about the US was a real threat. Wash soap, urine, milk, lemon juice, baking soda, starch and milk could all be used to write invisibly, and with Allied limitations on heat and chemical treatments to these letters two new types of papers emerged for sole use in prisoner writing papers: Sensicoat and Anilith. The Government Printing Office (GPO) created a clay based coating that would react to acid by turning green. The weight of the paper (56 lb) and the high cost to manufacture became the impetus to create the uncoated paper Anilith.

Censors claimed to find a small “putty like substance the size of a match head” concealed in various places in care packages addressed to German soldiers. This was a dry invisible ink being stashed in care packages. Again, GPO chemists created a coated paper processed with a water-sensitive formula that could detect all types of dry inks. This is believed to have cut down on a vast majority of all secret transmissions from US and Allied prisoner-of-war camps.

As we move from ink to digital we see use of many types of cryptography and steganography. A different type of digital invisible writing is being used today to secure your belongings: transparent micro-dots used in adhesive are almost impossible to remove short of firing them off. These microdots are being used on metals to prevent thieves from stealing wiring in homes being built and even railroad tracks. SelectaMark Security Systems makes an adhesive that is only visible in ultraviolet light. This can be painted onto your valuables and secured with coded microdots that are embedded in a nickel alloy or polyester that displays a code. Further security can come from embedding valuables with a microscopic form of synthetic DNA containing your information; so if your valuables are stolen and found you can be notified. Clearly the need to continue to keep messages safe from those who do not need to see them while getting them delivered safely to those who do remains a challenge that is as old as time.

–By Jae Mauthe, Archivist

Further Reading:

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/invisible-ink-history-wwi/