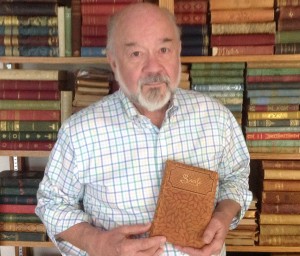

The American Bookbinders Museum recently received a generous library donation from Sidney F. Huttner a bookbinder and librarian. ABM Librarian, Amelia Grounds, interviewed Sid to find out a bit more.

Can you outline your career?

Well, I came to libraries both early — and a bit late. I was born and largely lived in northwest North Dakota until my family moved to Spokane, Washington, in 1955. Books were not a prominent feature of the North Dakota landscape, though I was allowed to use the high school library and read my way through The Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe! In Spokane, I quickly found an after-school job as a bicycle messenger for Western Union. That office was near the public library, and even closer to the Inland Book Store, so I haunted one or the other while waiting for buses home. Then, as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, I had a job in the circulation department of the library. I acquired a reputation for formidable skill in finding mis-shelved books.

I won a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship and started a degree in Philosophy at Stanford, then returned to Chicago as an admission officer, supervised a dorm, completed an MA, and in 1970 took a job as “assistant head” of Special Collections. My first assignment was to move this department out of innumerable crannies, closets, and wire cages into the new Joseph Regenstein Library. I stayed ten years, then moved to Syracuse University as head of the George Arents Research Library, then to the University of Tulsa, and in 1999 to the University of Iowa as Head of Special Collections and University Archives. I retired in 2012.

When did you develop an interest in bookbinding?

My boss in Regenstein was the curator, Robert Rosenthal. Bob’s theory of management was that staff should exchange responsibilities every couple of years. So, after I supervised moving the collections, I was told I was henceforth responsible for conservation and preservation programs, including selecting books for rebinding by any of a number of binders and binderies. At the same time, a colleague, Margaret M. “Peggy” Smith, who had for a couple years been a binding student with Paul Banks at the Newberry Library, started a workshop in the department. Since I knew nothing about binding or conservation, I thought it would be wise to sign up. I fairly quickly became a reasonably inventive boxmaker and case binder; Peggy married and left for England; and since I had the keys to the department, the study group insisted I keep it going. Meantime I’d acquired the tools and residual supplies of Lester King, the basis of a bench I still keep semi-active.

Another influence was Sue Allen, who was just beginning her study of 19th-century American binding design and who was around the department constantly; the two of us hit it off. My habit of buying used books, now greatly sophisticated by working in Special Collections and fueled with a little extra cash, quickly lead me to buy binding manuals, which broadened into books of any kind about bookbinding. Starting about 1971, I was a pretty active buyer until we moved to Iowa in 1999: in 25+ years you can collect a lot of books!

Did you use the collection professionally or personally?

Both, really. I skimmed, if not read closely, most everything I acquired, and over time I got to know people in the Guild of Book Workers and a lot of binders and book conservators, even internationally. In 1977, I was gifted with an early American binding that lead to our A Register of Artists, Engravers, Booksellers, Bookbinders, Printers & Publishers in New York City, 1821-1842 (New York: Bibliographical Society of America, 1993, available from Oak Knoll Books). This story, which traces the book to Henry I. Megarey, is told in “A Tale of Two Boards: A Study of a Bookbinding,” Bonefolder 8 (2012), p. 36-53 (online at http://digilib.syr.edu/

When did you decide to give up the collection?

As I approached retirement, and faced an inevitable need to downsize, I realized that I had added little to it in nearly a decade — and that many of the books would be available to me after retirement in the University of Iowa Libraries since its collection, developed to support the University’s Center for the Book, was extensive. It also occurred to me that I could increase the depth of that collection by gifting books I had that the Libraries had not — which began a series of annual gifts through 2013.

Those gifts, however, left me with a considerable number of books Iowa did not need. I had been aware of the American Bookbinders Museum for several years, and of course the high interest in the arts and crafts of the book that has characterized the Bay Area for many, many years. While my contribution would be necessarily modest, helping create a broad, rich, study collection in San Francisco, seemed a very good thing indeed, and hence I’ve offered them to the Museum.

Do you plan to retain part of the collection?

You may be aware of my Lucile Project, now over 1300 copies of a single book. To support it, I’m keeping for the moment a few directories, bibliographies, and books that directly relate to it. This collection does not really make any sense outside an institution, so these items will likely go to a new home, one day, with the Luciles.

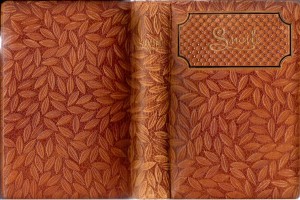

The bindings used to illustrate this article are from the Lucile Project collection: “…two padded embossed leather bindings by T. Y. Crowell. These “leathers” seem to have been recycled leather fragments (from old shoes, etc.) ground and mixed with adhesives. They are about paper-thick. They were then embossed, probably using a male/female set of dies — the level of detail must have be a devil to cut! — then stamped or tooled and used to create a padded (with felt pads) case. Much, much less expensive than a “real” leather binding, and relatively fragile, but satisfyingly attractive!”

Thank you, Sid, for your generous gift and the fascinating interview!

Library records to the gift can be found here.