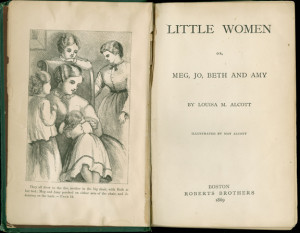

“Jo was the first to wake in the gray dawn of Christmas morning. No stockings hung at the fireplace and for a moment she felt as much disappointed as she did long ago, when her little sock fell down because it was crammed so full of goodies. Then she remembered her mother’s promise and, slipping her hand under her pillow, drew out a little crimson-covered book. She knew it very well, for it was that beautiful old story of the best life ever lived, and Jo felt that it was a true guidebook for any pilgrim going on long journey. She woke Meg with a “Merry Christmas,” and bade her see what was under her pillow. A green-covered book appeared, with the same picture inside….Presently Beth and Amy woke to rummage and find their little books also, one dove-colored, the other blue, and all sat looking at and talking about them while the east grew rosy with the coming day.” (Louisa May Alcott, Little Women)

It would be easy to assume that the impoverished March girls have received Bibles as their only Christmas present. However, it is likely their mother may have provided them with a book of scriptural readings designed for young people. (The Marches would have possessed one family Bible.) There were many such volumes among the plethora of books brought to market during the 19th century in England and American specially designed as gifts-to-be-given for the holiday season.

Newspapers of the day devoted columns to advertising these products during the season. For example, the Boston Post of December 18th, 1850 advertised the following:

Superb New Illustrated Works for Christmas and New Year’s Presents

Just published by D. Appleton & Co. 200 Broadway

1.Our Savior, with Prophets and Apostles

A series of Eighteen highly finished Engravings, designed expressly for this work, with descriptions by several American Divines. Edited by J.M. Wainwright, D.D. One volume imperial octavo, in the following varieties of binding:

Emblematic, with raised figure of our Lord, $7; Superantique beveled morocco extra, $10; Do col’d $15 [the same, colored]; Do. do. with miniature painting on each style of binding, on plate glass in centre, $15; Do, col’d $20; Do. Do. Papier mache framed in beveled morocco $12; Do. Col’d $18; Do. Plate glass, with superb painting on whole of sides, $25.

The publisher offers the book in a range of binding styles to suit every pocketbook; it is entirely possible that Marmee March, despite straitened circumstances, might have procured a simpler version of this book or something similar for her girls.

Beauty Inside and Out

Note that the advertisement above touts the high quality illustrations of the volume; gift books inevitably were illustrated with either wood cuts, steel engravings or both. New technology available after about 1810 made intricate steel cut engravings affordable to the masses.

The advertiser goes on to praise both the outer beauty of the book and the intrinsic value of its contents:

We can scarcely conceive of a work more commendable as a gift book, its interior and exterior being alike attractive to any person of pure and elevated taste. There is nothing ephemeral or perishable about it…it is a book, not for a season, for all time.

The clever copywriter has summed up the essence of the Victorian gift book: it was a status symbol for an increasingly literate population, first in England, in the first part of the century and then later in the United States. Elegant gift books made the perfect present for anyone aspiring to “pure and elevated taste.”

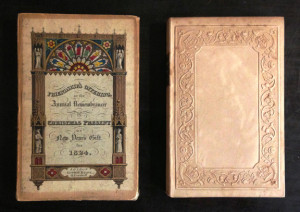

Whether read or not, a beautifully bound book could be shown off in the parlor; it was the coffee table book of the times. (One supposes that books bound with glass plates, as mentioned in the advertisement, were intended largely for display.) Lavishly produced gift books might have included ornate or embossed cloth, silk, or leather, a decorative frontispiece and end papers, an engraved presentation plate at the front, gilt edges, and a number of fine illustrations with hand-inserted tissue paper protectors. The volume might have had its own casing to keep it pristine. All of this was made possible by advances in machine-embossing, book stamping, engraving, and color lithography. Although machines made this luxury affordable for the middle class, the process of creating high end gift books was still very labor-intensive.

(photo via the University of Virgina/Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

Between the covers

Of course, any type of book could be elegantly bound and presented as a gift. However, the gift book phenomenon truly took off when publishers competed for the public dollar by commissioning anthologies of verse, short stories, moral essays, and original artwork.

A special type of gift book was the annual – an anthology of writings and original artwork artfully bound and printed, with the year stamped on the cover. These volumes were released to the public in months prior to the cover date, in order to be given as holiday gifts. They were also sold throughout the year for use as prizes in school competitions or to commemorate birthdays and anniversaries. Sub-categories of annuals included volumes for children, those espousing the abolitionist cause, and others representing various charities. A popular annual would appear in new editions for several years.

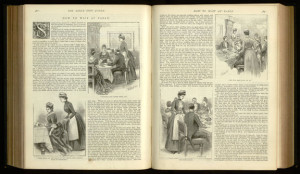

The desire for new material for these literary compilations was a boon to aspiring authors stateside. New writers might see their work published alongside established authors such as Longfellow, Hawthorne, and Emerson. In deference to the “pure and elevated taste” of the American reading public (particularly women), much of the content featured in anthologies was overly sentimental or romance based. In contrast, a portion of writing was given over to more meaty subjects, including mystery and horror (both Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Edgar Allen Poe contributed stories to gift books.) Atypical of these volumes was any actual Christmas content — these were books for Christmas, not about Christmas.

(photo from The Library of Birmingham’s copy of The Girl’s Own Annual 1887, pages 483-484. Parker Collection of Children’s Books BQ 0871.1 699955)

While they were a target audience for gift books, women also found their place as writers and editors for many of these publications; Mary Shelley and Harriet Beecher Stowe both contributed to annuals over the course of their careers.

Jo March, herself, (a thinly disguised Louisa May Alcott), helped her family by writing sensational short stories for public consumption:

“She…began to feel herself a power in the house, for by the magic of a pen, her “rubbish” turned into comforts for them all. The Duke’s Daughter paid the butcher’s bill, A Phantom Hand put down a new carpet, and the Curse of the Coventrys proved the blessing of the Marches in the way of groceries and gowns.”

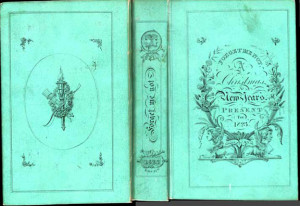

A British literary “Annual” for 1823, this Forget-me-Not was published late in 1822 for the holiday market. Many annuals had sentimental names evoking their character as gifts: The Gift, The Token, The Talisman, The Keepsake, to name a few. Illustrations with classical or romantic themes were typical. (photo from Wikipedia.)

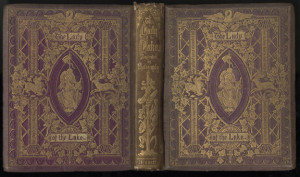

This edition of the beloved Scott poem displays the elegant binding of a high-end gift book. The Lady of the Lake, originally published in 1810, became a favorite gift book on both sides of the pond. The gold stamped cover includes the bookbinder’s initials (JL for John Leighton) within the centerpiece, indicating that he had standing above the usual bookbinders and artists who toiled to make these works of art. Unlike most gift books, this 1863 volume includes actual photographs. Image courtesy of Echoes from the Vault, a blog of the Special Collections at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland.

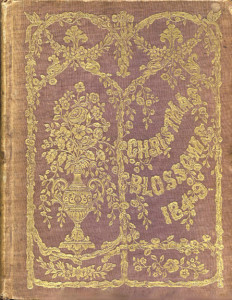

This American gift annual, the Christmas Blossom (1849) features gold stamping on blue rib-grain cloth. The words “Altemus Binder,” not visible here, are inserted into the garland at bottom left. From the website Publishers Binding Online 1815-1930: The Art of the Book.

Further suggested reading:

A great deal has been written on the subject of gift books, annuals, and their cousins, much of it quite academic. If you’re not particularly interested in exploring the “objective correlative” or “blurred lines of the vignette,” I recommend the following:

- A well-written and amusing essay on the gift book, its antecedents, and the variety of its bindings come from Kevin MacDonnell, “The American Gift Book” for the Antiquarian Bookesellers Association of America: http://www.abaa.org/member-articles/the-american-gift-book

- Another excellent overview is “Tokens of Affection: Art, Literature and Politics in Nineteenth Century American Gift Books” for Publishers’ Bindings Online: http://bindings.lib.ua.edu/gallery/giftbooks.htm

— Eleanor Boba

ABM Guest Blogger Eleanor Boba is a public historian who blogs about historic places off the beaten path and other curious matters. She lives in Seattle.