The duke said what he was after was a printing-office. We found it; a little bit of a concern, up over a carpenter shop — carpenters and printers all gone to the meeting, and no doors locked. It was a dirty, littered-up place, and had ink marks, and handbills with pictures of horses and runaway slaves on them, all over the walls. The duke shed his coat and said he was all right now.

— Mark Twain, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Twain’s imaginary print shop may well have used an iron hand press, a type of letterpress invented in the first part of the 19th century and favored by newspaper printers. Twain knew whereof he wrote. While a teen he worked as a typesetter and apprentice printer in his brother’s newspaper office in Hannibal, Missouri, going on to work in a variety of print shops around the country.

Like wooden presses, the iron press used movable type set in a frame, along with pre-cut graphic images such as woodblocks.

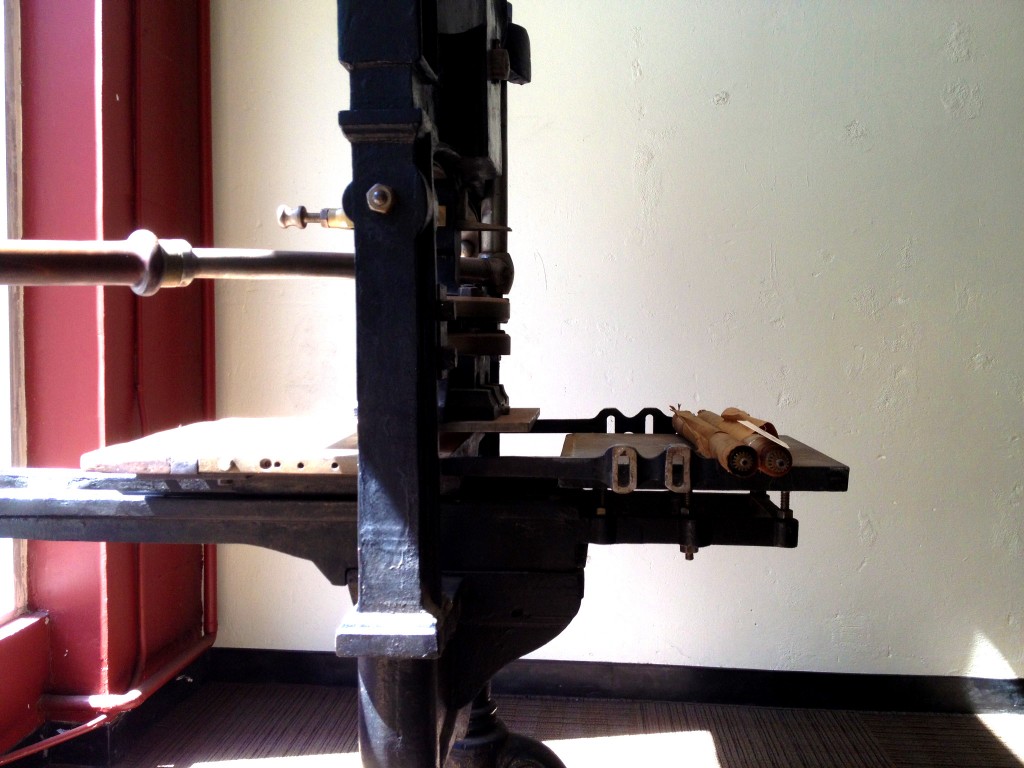

The iron hand press offered improvements over the four-centuries-old wooden press, although it never completely replaced it. Made of cast iron, it was of course sturdier, less susceptible to damage, and easier to clean of, say, ink stains than its wooden counterpart. But the real advantage came in the improvements that drove the ‘press.’ In place of the long wooden bar that had to be pulled by a brawny arm to bring the platen onto the type, the iron presses used a variety of levers, counterweights, and coils to lower and release the platen. Though brawn was still required, the amount of force required for each “pull” was less, allowing the work to go much faster; it also allowed larger sheets of paper to be printed at one go.

The first iron hand press in the United States was created by George Clymer in Philadelphia in 1813. His very ornate Columbia Press, covered with symbols of Americana, did not take off stateside. Moving to England Clymer found a much more receptive market. (Lord Stanhope had invented the very first iron press in 1800, so the British were familiar with the concept.) Within a few decades his press and a number of others modeled on it were common across Europe.

Eight years following Clymer’s invention, fellow American Samuel Rust designed a somewhat simpler iron press which he called the Washington Hand Press. Like Clymer’s press, the design was not proprietary; many manufacturers began offering the Washington press in the decades that followed. Improvements included steam power and a rotary printing surface. The iron hand press continued to be popular into the early years of the 20th century, although by this time it was often adapted as a way to get a quick proof for a job that would be printed on a more mechanized machine.

One notable advantage of the Washington press was its ability to be dismantled for shipment, an important matter for a heavy object in a far-flung country. As their names indicate, these presses were big and heavy. For example the famed Kelmscott Chaucer was printed by William Morris on an iron hand press standing seven feet tall and weighing over one ton. (Apparently no one is willing to obtain an exact weight on the machine.)[1]

The American Bookbinders Museum obtained its Washington press from the local Odd Fellows Hall in San Francisco. It was manufactured by Ostrander Seymour Company in Chicago about 1904. Rumor has it that it was last used by book designer and printer Adrian Wilson (1923-1988) in the City by the Bay, but this has not been substantiated. Considered one of this country’s significant book artists, Wilson designed and printed a number of books and booklets at his studio, “The Press of Tuscany Valley,” including the influential volume The Design of the Book. If, indeed, our press was used by Wilson, it would have been a secondary piece of equipment.

Meanwhile back in a fictional Mississippi backwater town, circa 1845, Twain’s con man turns out to be something of an artist himself:

[The duke] had set up and printed off two little jobs for farmers in that printing-office – horse-bills – and took the money, four dollars. He set up a little piece of poetry, which he made himself, out of his own head — three verses — kind of sweet and saddish — the name of it was, “Yes, crush, cold world, this breaking heart” – and he left that all set up and ready to print in the paper, and didn’t charge nothing for it.

— Eleanor Boba, Volunteer

[1] David W. Dunlap, “Mature, Muscular, Literary and Available,” New York Times, 5 Dec. 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/06/arts/design/kelmscott-press-a-thing-of-iron-musculature-is-to-be-sold.html?_r=0 (accessed 12 June 2014).