This week we have a guest feature from Marieka Kaye, Conservation Librarian and Book Conservator from the University of Michigan Library. In this article, she will be telling us about a book she’s recently been working on as a entry into exploring, briefly, the history of wove paper.

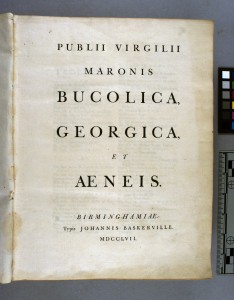

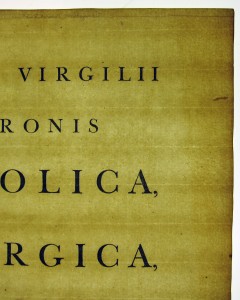

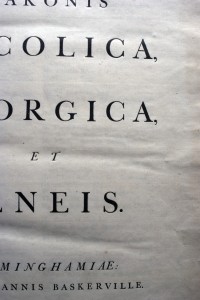

As a book conservator for a large university, I receive a wide array of rare books to work on. Often I have little time to look in depth at the history of the book at hand. When I first received a broken copy of a 1757 edition of Publii Virgilii Maronis Bucolica, Georgica, et Æneis, printed in Birmingham (England) by John Baskerville, my focus went more to how I was going to repair the broken sewing and flatten the severely warped boards. But when I opened the book I was immediately struck by the look, feel, and quality of the paper. When I looked closer I quickly realized that what I had on hand was the first example of wove paper made for western book production.

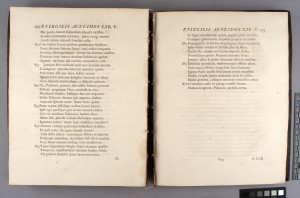

While bindings are meaningful and decorative, they are mainly there to serve the purpose of protecting the textblock inside. Paper is always something I pay close attention to when working on a book. Historically there have been two types of handmade paper, referred to as wove and laid. Wove paper is defined as a paper having a cloth-like appearance when viewed by transmitted light (Roberts & Etherington, 1982, p. 284). In handmade western paper, the finely woven wires in the papermaking mould achieved this quality. The mould was covered with a finely woven brass wire-cloth, which was referred to as brass vellum. This material was originally woven on a textile loom. While the paper historian Dard Hunter clearly explains that a wove paper was created and used in Asia for centuries prior, James Whatman I was likely to be the first to produce wove paper in the western world, and John Baskerville was the first known to use it in this work by Virgil (Hunter, 1978, p. 130-132).

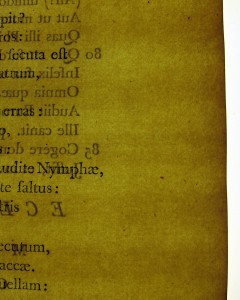

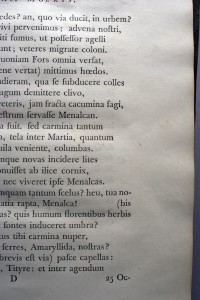

In contrast, laid paper shows thick and thin lines at right angles to each other, also produced by the layout of wires in the handmould. The closely spaced wires are the laid lines and the more widely spaced wires are the chain lines. It has long been thought that Baskerville wanted a smooth paper upon which his finely designed type would print more clearly and consistently, but Baker posits that comparing Baskerville type to the older Caslon and the fact that the Virgil text type is 18-point that really does not make sense. She thinks instead that Whatman experimented with laying a woven textile over a laid mould cover, in much the same manner used to make Asian wove paper. And Whatman may have offered this experimental wove paper to Baskerville to try out. In fact, it was Baskerville who glazed (plated) the printed sheets after printing, which gives the papers – wove and laid – a smooth, polished surface that resembles parchment vellum.

Baskerville’s Virgil is not completely made up of wove paper, as seen in the photos above. The textblock is partially made up of wove and partially made up of laid paper. It is thought that Whatman was unsatisfied with his early wove paper, and he and his son, James Whatman II, continued to perfect it. When looking closely at the paper in the Virgil, the pattern of the warp (chain) wires is very clear. A special loom for weaving wire was eventually developed, but not for another 20+ years. Change came slowly as Europeans had been using laid paper for more than 500 years before Whatman began developing this new variety for use in the book trade and for artists. Styles and attitudes had to change before wove became the dominant paper type in the age of machine-made papers.

Benjamin Franklin first exhibited wove paper in 1777 in France (Wroth, 1964, p. 125). It was mentioned, although not explicitly named, in a note appended in Elegiac Sonnets and Other Poems by Charlotte Turner Smith, printed by renowned printer/publisher (and historian) Isaiah Thomas in 1795 (Baker, 2010, p.100). Speaking about the first time he personally used wove paper, Thomas wrote:

The making of the particular kind of paper on which these sonnets are printed, is a new business in America; and but lately introduced into Great Britain; it is the first manufactured by the editor” (Wroth, 1964, p. 126).

It was slower to catch on in the more conservative America, although there is evidence of it being used for printing currency in Maryland, dated December 7, 1775 (Wilcox, 1911, p. 46). Eventually wove paper became the predominant type of handmade paper about 50 years later (c. 1810), holding its ground to the present day in current machine-made papers. Today more than 99% of the world’s paper is of the wove variety (Balston).

– Marieka Kaye, Conservation Librarian/Book Conservator, University of Michigan Library

References:

Balston, John. The Whatmans and wove paper. Retrieved March 25, 2015 from http://www.wovepaper.co.uk/index.html.

Baker, Cathleen A. (2010). From the hand to the machine: Nineteenth-century American paper and mediums: Technologies, materials, and conservation. Ann Arbor: The Legacy Press.

Baker, Cathleen A. (2019). “The wove paper in John Baskerville’s Virgil (1757):

Made on a cloth-covered laid mould.” In Papermaker’s Tears: Essays on the Art and Craft of Paper. Vol. 1. Ed. Tatiana Ginsberg, 2–44. Ann Arbor: The Legacy Press.

Hunter, Dard. (1978). Papermaking: The history and technique of an ancient craft. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Roberts, Matt T. and Etherington, Don. (1982). Bookbinding and the conservation of books: A dictionary of descriptive bibliography. Washington, DC: Library of Congress.

Wilcox, Joseph. (1911). Ivy Mills, 1729-1866: Wilcox and allied families. Baltimore: Lucas Brothers, Inc.

Wroth, Lawrence C. (1964). The colonial printer. Charlottesville: Dominion Books/University Press of Virginia.