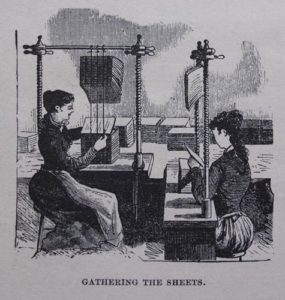

In over a year of giving tours at the American Bookbinders Museum, I have spoken about the women in mid-19th-century binderies who sewed books, day in and day out. Speed was of the essence: By the mid-1800s many of the time-consuming processes of binding had been mechanized, increasing production capacity hugely. The bottleneck? Sewing. So compromises were made in the way books were sewn in order to move that process along faster. A skilled worker on the sewing floor was expected to sew 200 books a day.

Think about that. In a ten hour day, that’s twenty books an hour.

In order to do that, the sturdy practice of sewing around cords was replaced with sewing past them: notches were cut in the spines of books and the book-sewer ran the thread into a signature, out the notch, in back of the cord, back into the notch, and so on. When pulled tight, the thread pulled the cords into the notches. The rub, in terms of quality, was that there was nothing to hold the cord there; if a thread broke, the cord could pop out and the book fall apart. Still, it was fast. Twenty-books-an-hour fast.

Which is where I come in. For five days this fall (spread out over five weekends), as a way of piquing interest in the history of binding and in the ABM, I appeared at San Francisco’s Dickens Christmas Fair in the role of one of those workers. My first conclusion: If paid by the piece–which one often was–I might have starved to death before I reached any decent speed. Even with five days of working at my new skill, I was unable to do more than eight books an hour. As with many hand skills, the process is much more complex than it looks, and attempting to do it properly takes focus.

Which is where I come in. For five days this fall (spread out over five weekends), as a way of piquing interest in the history of binding and in the ABM, I appeared at San Francisco’s Dickens Christmas Fair in the role of one of those workers. My first conclusion: If paid by the piece–which one often was–I might have starved to death before I reached any decent speed. Even with five days of working at my new skill, I was unable to do more than eight books an hour. As with many hand skills, the process is much more complex than it looks, and attempting to do it properly takes focus.

Focus comes hard when you’re sitting on a busy by-way, talking about binding to everyone who comes by. Parents with children–especially very small children–would stop to watch. A startling number of people who took bookbinding in middle-school (who knew?) came by to reminisce. Older kids sometimes seemed jaded about the process until I pointed out that, because of the “new-fangled machinery,” books were becoming inexpensive enough that even a poor Factory Girl like me could own one. Some people just wanted to sit on a nearby bench and watch for a while. Many people took photos or video, some asked me about the paper and thread I was using, or thought I might be tatting. In character as Annie, an Irish bindery worker, I answered all the questions I could, and steered people to the ABM brochures you can see in the basket on the left.

Staying in character and yet trying to give some of the background on where sunken-cord sewing fit into the history of 19th century binding, I sometimes had to resort to my character’s Celtic second-sight: Dickens Fair is set sometime around the 1850s, and the first successful book sewing machine would not be patented until 1871. “This is the only way it’s done now, but in a decade or two, you wait. They’ll find a way to build a machine to do the sewing too.”

In order to conserve materials, I would wait until I had used up all my signatures, then pull them off the cords, cut the threads, and start all over again. Even for that I had a story: “We’ve a new girl at the bindery, just learning the work, and sometimes I have to take her books apart and sew ’em again.”

It’s not often you get to be the problem and the solution.